India's banks poised for double-digit loan growth as economy gains traction

Indian banks are set to expand lending and improve their net interest margins in 2022 as they benefit from the nation's economic recovery.

"Indian banks are ready to shift into a growth phase, just in time to meet rising demand as the country's economy recovers," said Nikita Anand, associate director for credit risk at S&P Global Ratings. "Faster loan growth will be bolstered by improving asset quality and a normalization in credit costs over the next 12-18 months."

Overall bank credit growth accelerated to 9.2% year over year in December, according to Reserve Bank of India data in a Jan. 14 report. That compared with 5.2% growth in March 2021. HDFC Bank Ltd., India's largest private sector bank, said its total advances as of Dec. 31, 2021, increased 16.5% year over year.

The World Bank expects India's economy to grow 8.3% for the current financial year ending in March, and 8.7% next year, according to the Global Economic Prospects report released Jan. 11. In contrast, global economic growth is likely to slow amid the surge of cases of the omicron variant of COVID-19, and higher inflation, debt and income equalities, the World Bank said. India's GDP grew 8.4% year over year in the July-to-September quarter, reversing a 7.4% contraction from a year ago, according to government data released Nov. 30.

Better balance sheets and an appetite for small and medium-sized enterprise lending can raise overall bank credit growth to more than 10% in 2022 and to between 12% and 13% thereafter, Jefferies said in a Jan. 4 report. Bank credit growth improved steadily in 2021 thanks to stronger retail demand, economic recovery and an inflationary push, Jefferies noted.

Stronger footing

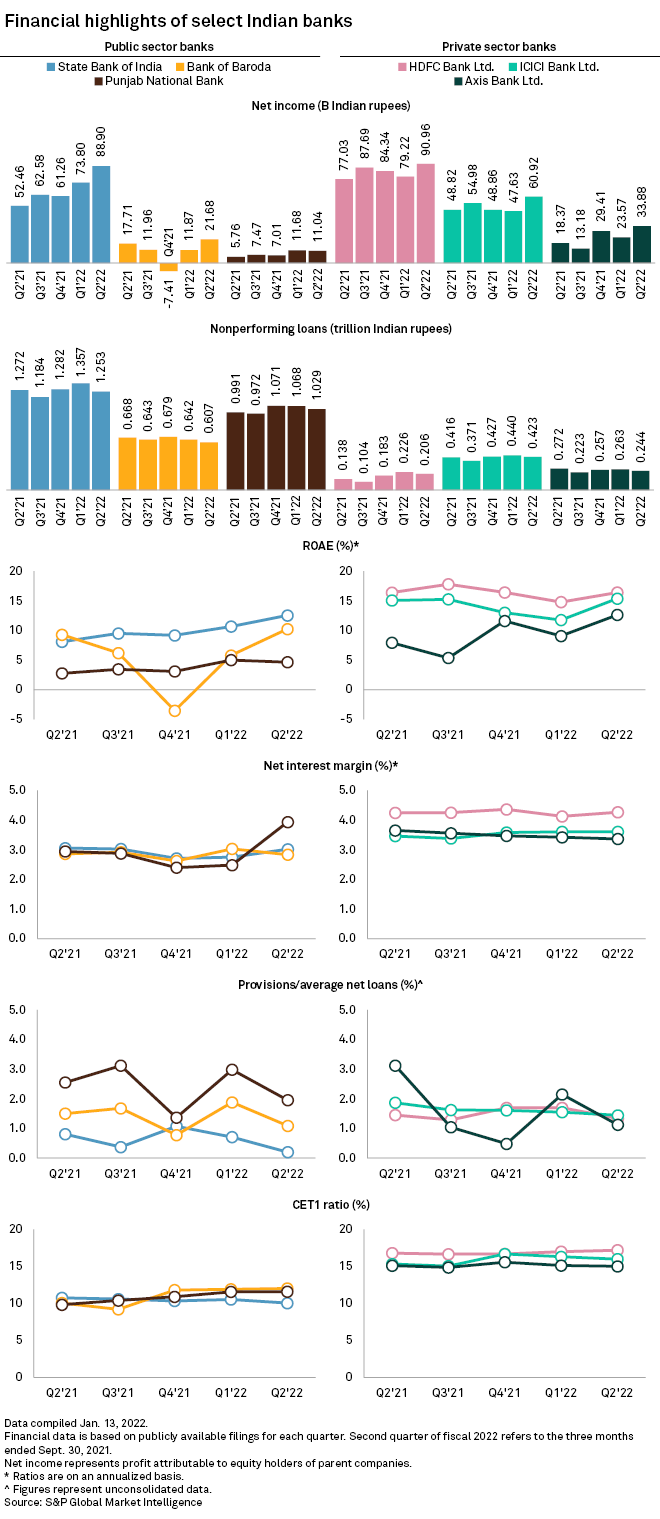

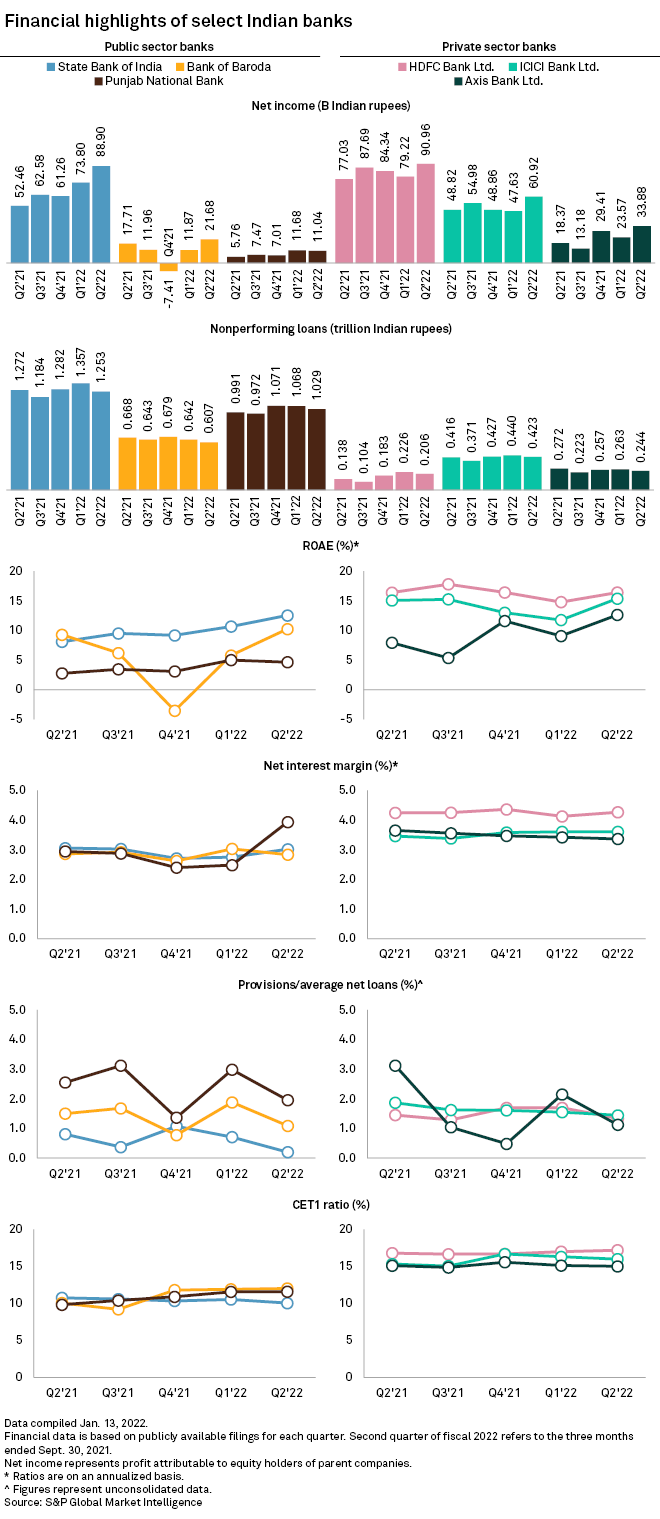

"Economic activity in India remains strong, with upbeat consumer and business confidence and upticks in several incoming high frequency indicators," according to a Jan. 17 report by the central bank's economists. The aggregate capital to risk weighted assets ratio of Indian banks strengthened to 16.6% at end-September 2021, from 14.8% in March 2020. Their return on assets climbed to 0.8% from 0.2% in the 18-month period, it said.

Their return on assets climbed to 0.8% from 0.2% in the 18-month period, it said.

Banks can now focus on credit growth after spending the previous years on monitoring their asset quality, said Nitin Aggarwal, a research analyst at financial services firm Motilal Oswal. After reducing their bad loans, banks are now better prepared. "We have not seen as much of stress on the corporate side," Aggarwal said.

Asset quality

The banking sector improved asset quality in 2021 with the ratio of gross NPAs down to 6.9% at the end of September, from 8.2% at the end of March 2020, according to the Reserve Bank of India, or RBI. Stress tests conducted by the central bank predict aggregate nonperforming assets to rise to 8.1% by September under a baseline scenario and to 9.5% under a severe stress scenario as overall lending grows. Still, all banks would be able to comply with the minimum capital requirements even under severe stress scenarios, the RBI said in a December 2021 report.

"We do not see much fresh stress build up even from the new COVID wave, which does not seem to be severe enough to induce full scale lockdowns," said Emkay Global banking analyst Anand Dama. Most of the bigger-ticket bad loan formation is a thing of the past, Dama said.

The government will likely step up infrastructure spending and announce incentives for the agriculture and manufacturing sectors in its budget for the next financial year that will be presented Feb. 1. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will likely continue the government's support for growth even as she seeks to keep fiscal deficit in check, Nomura analysts Sonal Varma and Aurodeep Nandi wrote in a Jan. 21 note.

"The government's fiscal policy since the pandemic began has prioritized growth and fiscal transparency over fiscal consolidation, in the hope that robust medium-term growth prospects will help with debt sustainability," Nomura wrote. The government will likely announce it is on course to meet its fiscal deficit target of 6.8% of GDP in the current fiscal year ending March 31, and set a target of 6.4% for next year, Nomura noted.