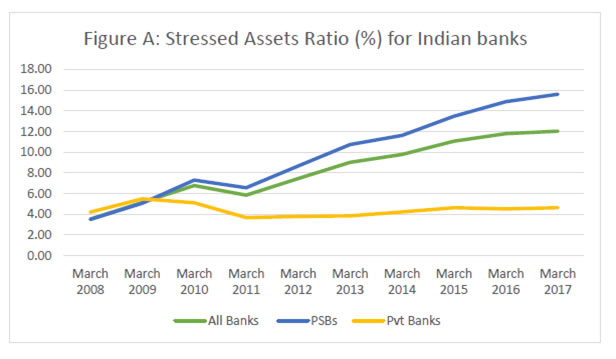

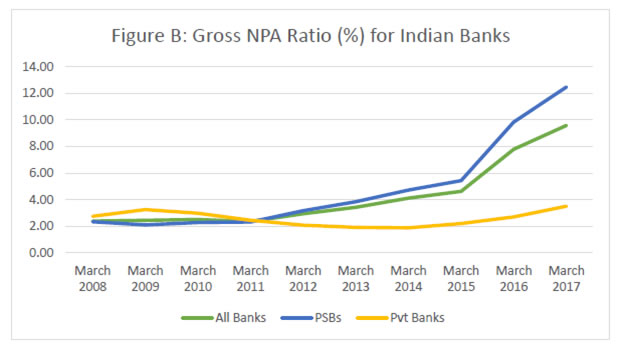

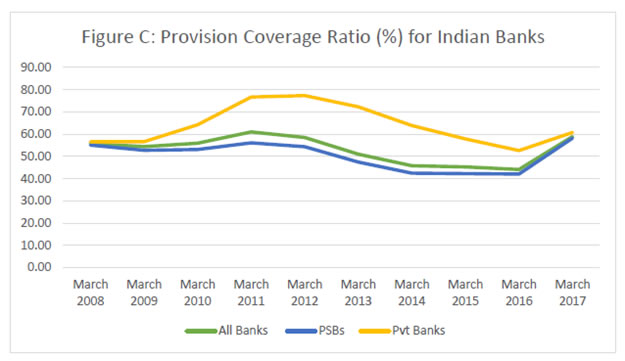

I would like to contend that a primary cause for the recent slowdown in our growth is the stress on the banking sector’s balance-sheet, especially of public sector banks. As Figures A and B show using the Reserve Bank’s data, the stress in bank assets has been mounting since 2011 and has now materially crystallized in the form of non-performing assets (NPAs). Some banks are under the Reserve Bank’s Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) having failed to meet asset-quality, capitalization and/or profitability thresholds; others meet these thresholds for now but are precariously placed in case the provisioning cover for loan losses against their gross non-performing assets (Figure C) is raised to international standards and made commensurate with the low loan recoveries in India.

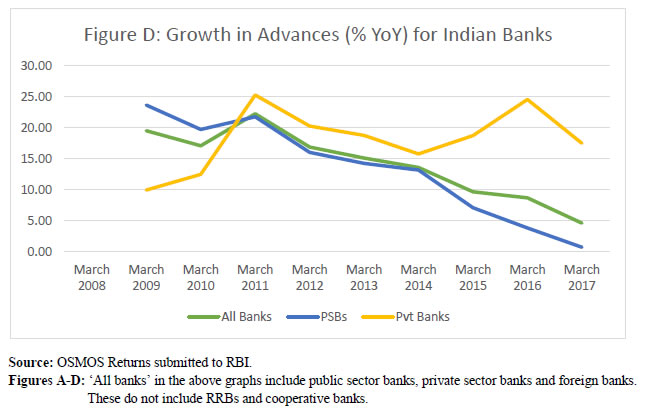

When bank balance-sheets are so weak, they cannot support healthy credit growth. Put simply, under-capitalized banks have capital only to survive, not to grow; those banks barely meeting the capital requirements will want to generate capital quickly, focusing on high interest margins at the cost of high loan volumes. The resulting weak loan supply (see in Figure D, the steady decline in loan advances growth since 2011 for public-sector banks), and the low efficiency of financial intermediation, have created significant headwinds for economic activity.

A decisive and adequate bank recapitalization, options for which I will lay out (again) at the end of my remarks, is a critical intervention necessary to address this balance-sheet malaise.

In a recent study from the Bank for International Settlements, Leonardo Gambacorta and Hyun-Song Shin (2016) document that bank capitalization has a strong effect on bank loan supply: a one percentage point increase in a bank’s equity-to-total assets ratio is associated with a 0.6 percentage point increase in its yearly loan growth. In fact, if a banking system remains systematically undercapitalized and new lending is not kept under a tight supervisory watch, then the economy can suffer significantly from a credit misallocation problem, now commonly known as ‘loan ever-greening’ or ‘zombie lending’. In particular, undercapitalized banks have an incentive to roll over loans from financially struggling existing borrowers so as to avoid having to declare these outstanding loans as non-performing. With these zombie loans, the impaired borrowers acquire enough liquidity to be able to meet their payments on outstanding loans. Banks thus avoid the short-run outcome that these borrowers might default on their loan payments, which would lower their net operating income, force them to raise provisioning levels, and increase the likelihood of them violating the minimum regulatory capital requirements. By ever-greening these loans, banks effectively delay taking a balance-sheet hit, while taking on significant risk that their borrowers might not regain solvency and remain unable to repay, now even larger loan payments. While unproductive firms receive subsidized credit to be just kept alive, loan supply is shifted away from more creditworthy firms.

Adequate bank, more generally, financial intermediary, capitalization is thus a pre-requisite for efficient supply and allocation of credit. Its central role in supporting economic growth is consistent with what other economies and regulators have experienced in the past episodes of banking sector stress. I will cover briefly the Japanese crisis in the 1990s and early 2000s, and the European crisis since 2009. Professor Ed Kane (1989), Boston College, had reached similar conclusions for the United States based on the Savings and Loans crisis of the 1980s.

The Japanese story

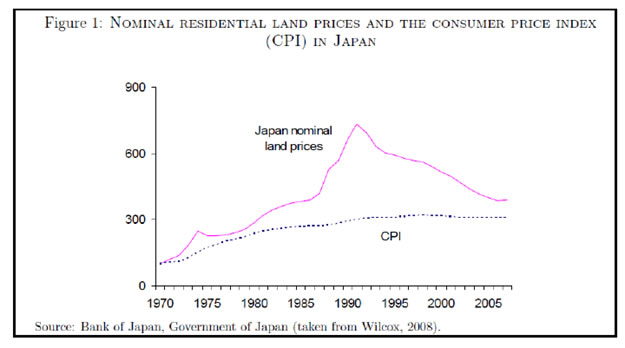

In the early 1990s, a massive real estate bubble collapsed in Japan (see Figure 1). This caused problems for Japanese banks in two ways: first, real estate assets were often used as collateral; second, banks held the affected assets directly, so that the decline in asset prices had an immediate impact on their balance sheets. These problems in the banking system quickly translated into negative real effects for borrowing firms along the lines I laid out above.

Subsequently, the Japanese government introduced several measures to stabilize the banking sector and spur economic growth. Among these measures were a series of direct public capital injections into impaired banks, mostly in the form of preferred equity or subordinated debt. However, as conclusively shown by Table 1 from Takeo Hoshi and Anil Kashyap (2010), bulk of the injections came after 1999, close to a decade after the collapse; the economic scale of earlier recapitalizations was small relative to that of banking sector’s real estate exposure so that these half-hearted measures failed to adequately recapitalize the Japanese banking sector.

| Table 1. Capital injection programmes in Japan (in trillions of yen) | ||

| Legislation | Date of injection | Amount injected |

| Financial Function Stabilization Act | 3/1998 | 1.816 |

| Prompt Recapitalization Act | 3/1999-3/2002 | 8.605 |

| Financial Reorganization Promotion Act | 9/2003 | 0.006 |

| Deposit Insurance Act | 6/2003 | 1.960 |

| Act for Strengthening Financial Functions | 11/2006-3/2009 | 0.162 |

| Source: Hoshi and Kashyap (2010). | ||

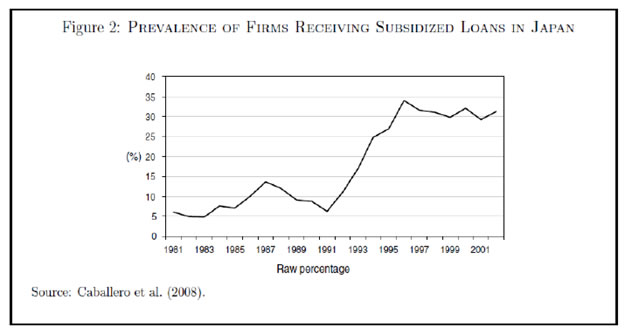

Joe Peek and Eric Rosengren (2005) were among the first to provide evidence that this inadequate recapitalization of the Japanese banking sector had major consequences for the allocation of credit to the real economy. Specifically, they showed that firms were more likely to receive additional loans if they were in fact in poor financial condition. They interpreted this finding as being consistent with the ‘zombie lending’ incentives of undercapitalized banks. Figure 2 shows that the percentage of zombie firms increased from roughly 5% in 1991 to roughly 30% in 1996. In related work, Mariassunta Giannetti and Andrei Simonov (2013) found that banks that remained weakly capitalized after the introduction of the recapitalization programmes provided loans to impaired borrowers, while well-capitalized banks increased credit to healthy firms. The authors estimated that the credit supply to healthy firms could have been 2.5 times higher in 1998 if banks had been recapitalized sufficiently.

In turn, this misallocation of loans translated into significant negative effects for the real economy. Because zombie lending kept distressed borrowers alive artificially, the respective labor and supply markets remained congested; for example, product market prices were depressed and market wages remained high. Sectoral capacity utilization also remained low, which destroyed the pricing power and attractiveness of investments for healthy firms competing in the same sectors. Ricardo Caballero, Takeo Hoshi and Anil Kashyap (2008) showed that, as a result of these spillover effects, healthy firms that were operating in industries with a high prevalence of zombie firms had lower employment and investment growth than healthy firms in those industries that did not suffer from zombie firm distortions. They estimated that due to the rise in the number of zombie firms, typical non-zombie firm in the real estate industry experienced a 9.5% loss in employment and a whopping 28.4% loss in investment during the Japanese crisis period.

The European story

In recent years, the Eurozone has been following a similar path to that of the Japanese economy in the 1990s and early 2000s. Starting in 2009, countries on the periphery of the Eurozone drifted into a severe sovereign debt crisis. At the peak of the European debt crisis, in 2012, anxiety over excessive levels of national debt led to interest rates on government bonds issued by countries in the European periphery that were considered unsustainable. For instance, from mid-2011 to mid-2012, the spreads of Italian and Spanish 10-year government bonds increased by 200 and 250 basis points, respectively, relative to German government bonds. Since this deterioration in the sovereigns’ creditworthiness fed back into the financial sector (Acharya et al, 2015), lending to the private sector contracted substantially in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain (the ‘GIIPS’ countries), as shown in Figure 3. In Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, for example, the volume of newly issued loans fell by 82%, 66%, and 45% over the 2008–13 period, respectively.

However, the impact of the European debt crisis on bank lending is more complex than in the case of the Japanese banking crisis, which was mainly caused by the bursting of an asset price bubble and the resulting impairment of banks’ financial health. While the European debt crisis also caused a hit on banks’ balance sheets due to the substantial losses on their sovereign bond-holdings, in addition it created gambling-for-resurrection incentives for weakly capitalized banks from countries in the European periphery. These banks sought to increase their risky domestic sovereign bond-holdings even further as they were an attractive bet to rebuild capital quickly given zero risk-weights. This incentive led to a crowding-out of lending to the real economy, thereby intensifying the credit crunch (Acharya and Steffen, 2014).

No comments:

Post a Comment