Six Advantages of Hyperbolic Discounting…And What The Heck Is It Anyway?

I was tossing around concepts for an article, when I decided to settle on the issue of hyperbolic discounting. True to my collaborative self, I shared the title with an industry professional, and here’s what he emailed back:

WTF is HyerpWTF&$*R.. Love it.

So, these are the reasons I chose the subject of hyperbolic discounting:

- A lot of people have no clue what hyperbolic discounting is.

- A lot of people are not aware of the vast ramifications that hyperbolic discounting has on society as a whole.

- A lot of people do not use the power of hyperbolic discounting in conversion optimization.

Hyperbolic discounting is a phrase that’s often met with a “WTF?!” or a confused gaze. Yet, it’s one of those concepts that can blow your conversion optimization to a whole new high.

What Is Hyperbolic Discounting?

Since the phrase hyperbolic discounting is despicable jargon, let me explain it in terms that even I can understand.

Hyperbolic discounting happens when people would rather receive $5 right now than ten bucks in a month. That’s it. People value the immediacy of time over the higher value of money.

Expressed another way, hyperbolic discounting is a person’s desire for an immediate reward rather than a higher-value, delayed reward.

Stating it in such simple terms loses some of the complex nuances of the principle. You’re probably thinking, “Shoot, those people are stupid. I’d take the ten bucks. Who cares if I have to wait?”

But, here’s the thing: Hyperbolic discounting is a cognitive bias, meaning that it is an ingrained mental snafu that defies logic and common sense. When hyperbolic discounting is framed differently, it has incredible power.

The power of the mental hurdle adjusts based on the time involved. Here’s how one psychology site expressed it:

If someone were to offer you the choice between $50 right now or $100 tomorrow, the latter would seem the clear choice. But, as the delay gap widens, the importance of the extra $50 quickly diminishes for most people, despite the fact that its actual value is constant.

For instance, confronted with a choice between $50 today or $100 one year from now, would you still wait for the $100? Statistically speaking, the vast majority will take the $50.

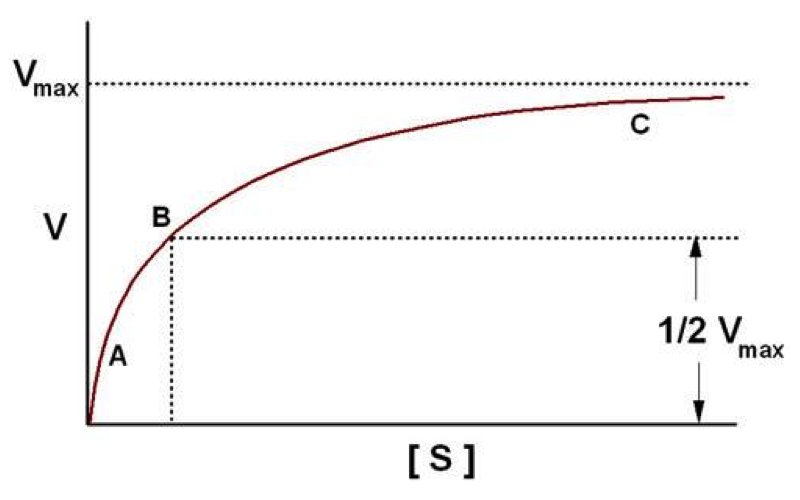

But, the pattern follows a hyperbola, so once a certain time threshold is crossed, the devaluing effect of time diminishes. For example, most will opt to take $100 in ten years over $50 in nine years.

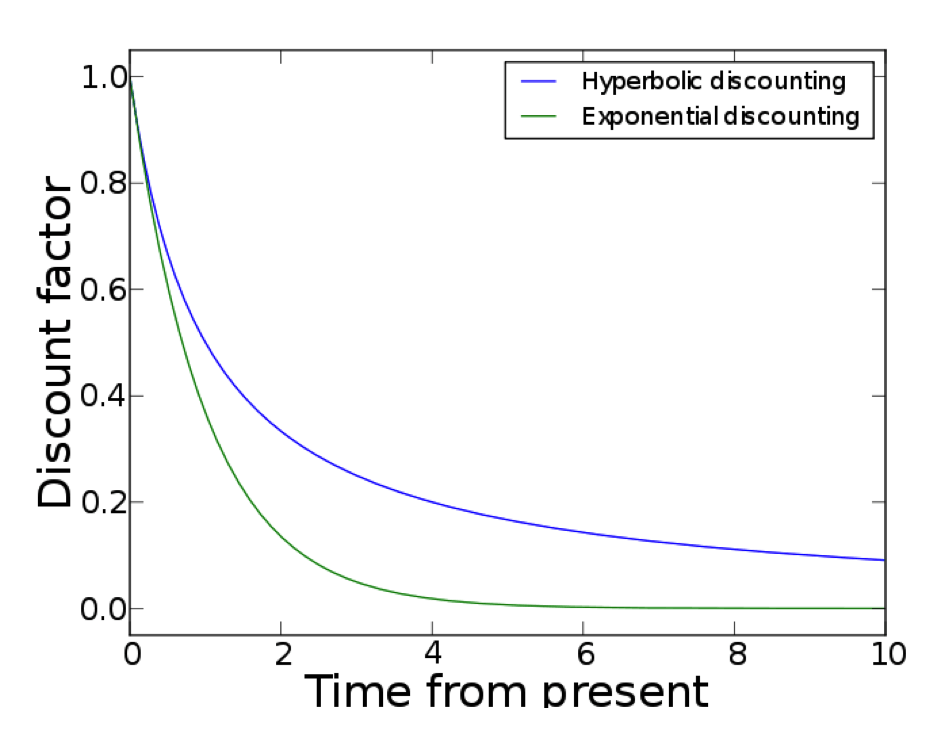

That’s where the hyperbola part of hyperbolic discounting comes in. A hyperbolic curve displays the effect of hyperbolic discounting, in contrast to an exponential curve.

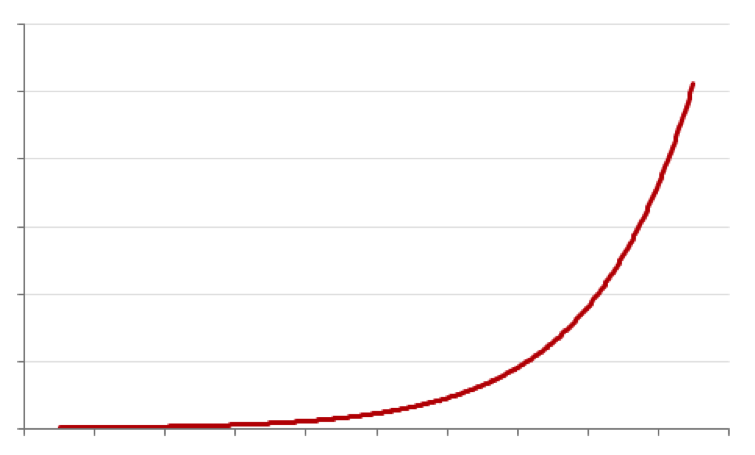

This is an exponential curve:

This is a hyperbolic curve:

Hyperbolically, the discount factor diminishes based on the amount of time that elapses.

Hyperbolic Discounting Truly Works

Hyperbolic discounting isn’t some nifty gimmick that sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. Our neurological cognitive selves are programmed in such a way that we are not immune to the tug of hyperbolic discounting.

We can combat it by way of reasoning. However, the neuroscience behind the bias shows us that we can’t completely ignore hyperbolic discounting.

According to neuroscience, “The true objective of the brain is to maximize the rate of reward.” In other words, the brain has a built-in mechanism that produces a greater desire for present satisfaction.

In the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers discovered that the “durations of saccades of varying amplitude can be accurately predicted by a model in which motor commands maximize expected discounted reward.” To explain this in layman’s terms, the brain makes discounting judgments reflexively and automatically. We don’t have to reason through it; we just want it.

Only by analyzing a situation objectively using coherent reasoning power is a person able to ferret out the cognitive bias and squash it.

Some scientists explain hyperbolic discounting through an evolutionary approach. If your loincloth-wearing hunter-gatherer ancestors found food, they would kill it and eat it right away. They wouldn’t let the scrawny antelope pass in order to possibly get a fatter one later. They would get the scrawny one now. One little antelope meal in the tummy is better than two fat ones in a month. By that time, the rugged hunter-gatherer would die.

Imagine a dehydrated person traveling through the desert. Ahead, they see a small glass of water. If they deny the sip of water and keep going just a little longer, they will receive one hundred water bottles. What do they do?! Hyperbolic discounting impacts them positively, allowing them to sustain life by choosing a little bit now rather than a lot later.

The Power of Now

Copywriters, psychologists, and moms understand this phenomenon all too well. We want what we want, and we want it now.

In the famous marshmallow experiment, Stanford psychologists led a child into a room and offered the child a single marshmallow. The treat was sitting there on a table right in front of them. If the child could wait fifteen minutes without eating the marshmallow, they would receive a second marshmallow.

Yes, I know, borderline abusive.

Although most children were able to keep their appetite in check, the study highlighted an issue that is known as delayed gratification. Ooh. Tough one! I know many adults who would have eaten the first marshmallow as soon as they saw it.

Delayed gratification is the behavioral opposite of hyperbolic discounting. Delayed gratification means “making a choice which limits the ability of getting something now, for the pleasure of being able to have something bigger or better later.

It’s a concept that goes against the ingrained ideals of culture — the whole “we want it now” idea.

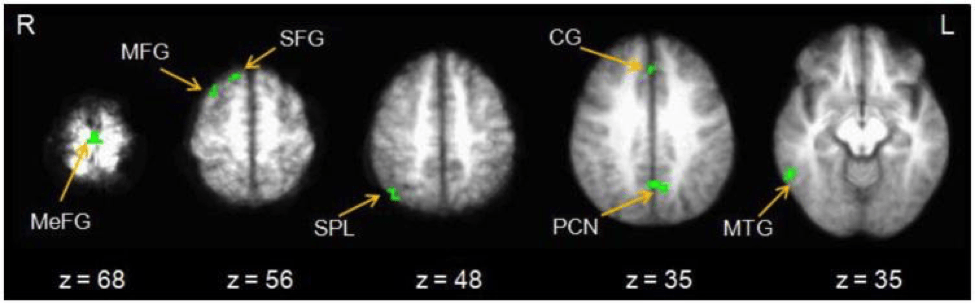

Our brains are wired for now. Neuroscientists have discovered that our brains light up like a Fourth of July night when we get stimulated by the power of something right now.

The brain uses hyperbolic discounting as a learning mechanism. The basal ganglia contain a responsive portion that learns by receiving immediate reward-based feedback.

Scientists agree that the brain’s objective is to “maximize the expected value of reward.” The way the brain maximizes the expected value is by getting it sooner rather than later.

Hyperbolic Discounting! It’s Everywhere!

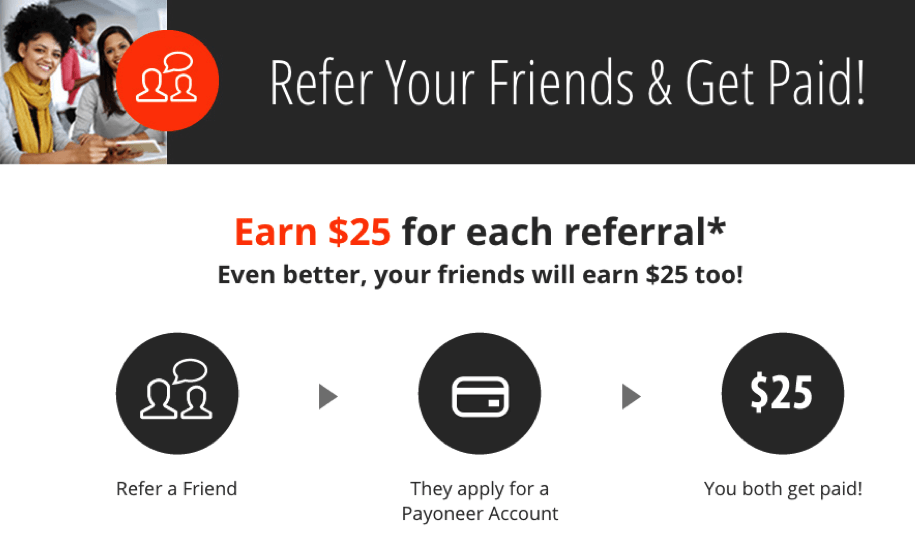

When was the last time you saw this technique in use? I just saw it, just now, on a site where I was conducting research for this article:

But, apart from sales gimmicks and advertisements, this cognitive bias has devastating effects elsewhere in life.

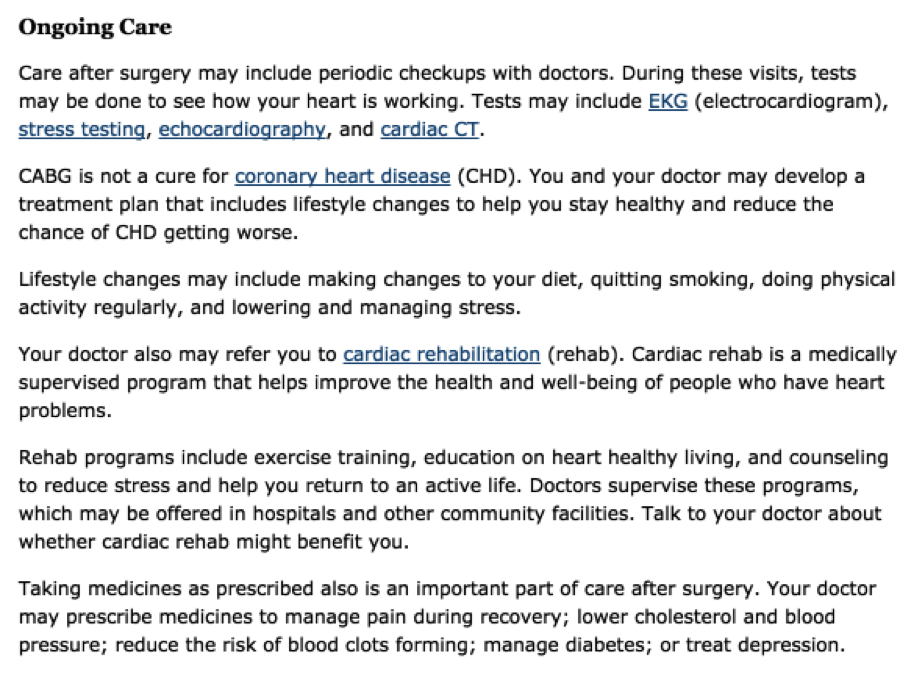

Each year, hundreds of thousands of people receive coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. The surgery saves their lives. But, it saves their lives for the long term only if they apply the correct lifestyle changes. What kinds of changes?

Here’s how the National Institutes of Health puts it:

No smoking. More activity. Healthier diet. Faithfully taking meds. Tragically, however, “Ninety percent of those patients decide to forego survival and comfort in favor of the short-term pleasures of unhealthy foods and laziness” (source).

Why? Hyperbolic discounting.

Substance abuse? Yes, there’s another indication of the malevolence of hyperbolic discounting. Get high now. Forget about the results until later.

Let’s take another massive example. It’s not as morbid, but it’s equally devastating: Credit cards. Credit cards push hyperbolic discounting to the max. A buyer can have something of value now! Just buy it on credit! Or, they can wait and save the money they end up paying in scandalous interest rates.

Credit is one of the most damaging financial tools ever to enter the world. Millions of people are trapped in a vortex of debt because of the principle of hyperbolic discounting.

I’m not here to rail against the credit card industry. I’m merely pointing out the vast and mind-blowing extent of hyperbolic discounting.

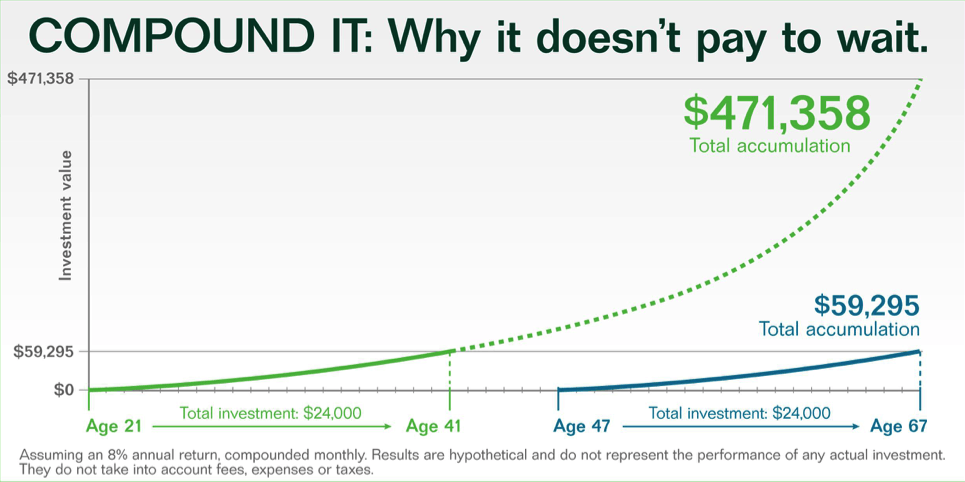

Let me share another world-shaking manifestation of hyperbolic discounting in play. Why don’t most people save for retirement? Because there’s no immediate reward for saving for the future!

If you could go out to eat at a nice restaurant for $200 tonight, then why the heck would you put that money in some retirement fund to enjoy when your 72?!

But, all that waiting has its own hyperbolic curve, and it’s not very pretty.

You see what happens? It’s hard for people to deny themselves now in order to enjoy a reward later.

Hyperbolic discounting is dreadfully powerful. I would never advise any marketer to exploit the hyperbolic discounting principle in harmful ways.

I’ve used the above examples to show the incredible power of hyperbolic discounting, but I also want to use them as a warning. On a macroeconomic scale, hyperbolic discounting can have devastating results. On a smaller scale — conversion optimization, ecommerce, etc. — the results are innocuous, beneficial, and appropriate.

Put Hyperbolic Discounting to Work

Are you ready to harness this cognitive bias to the conversion machine? Keep in mind, this is tame stuff. There are no coronary bypasses or credit card retirement scandals going on here. This is honest work, and here’s how it’s done:

1. Raise your price. Wait for the reward.

Hyperbolic discounting gives you license to raise your price as long as you delay payment.

When you offer to postpone the payment, the price of the item becomes less relevant to the buyer. Here’s why. As soon as they realize they don’t have to pay right away, the customer doesn’t think about paying. Instead, the hyperbolic power of the availability of the product dominates their thinking.

Now, instead of thinking, “Wow! That’s expensive!” the buyer is thinking “Wow! I can have it now!” Based on the hyperbolic principle, the wow-I-can-have-it-now thought is going to win out.

As soon as the price consideration exits to stage left, the buyer is ready to make their purchase, even if it costs them a lot of money (someday). You’re ready to profit.

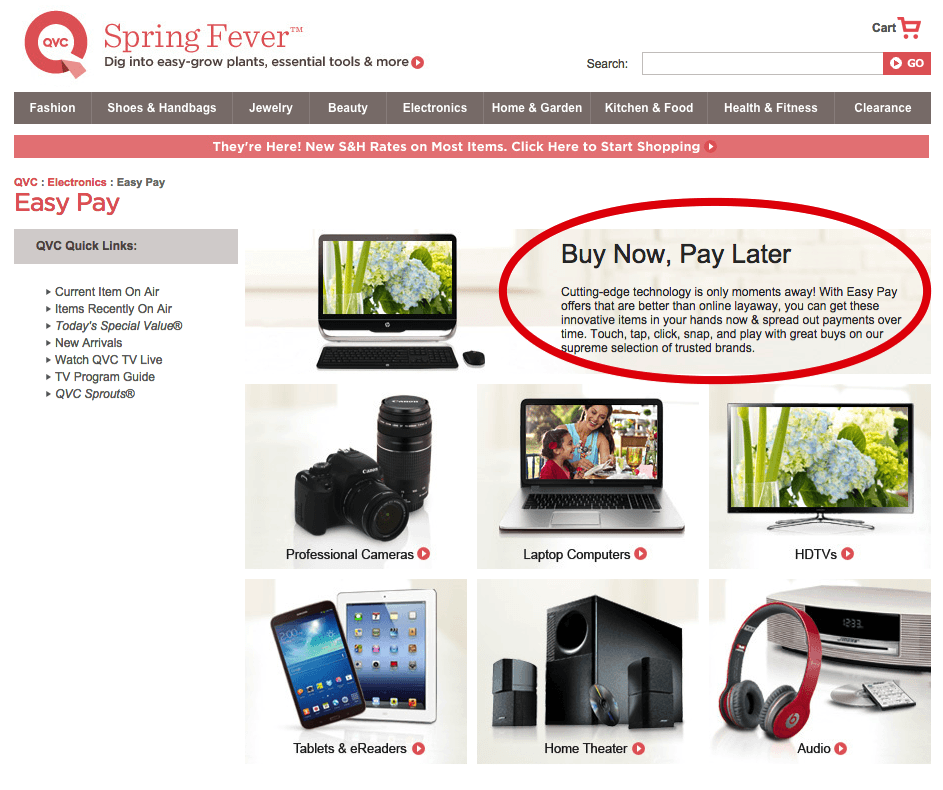

2. Advertise this: Buy now. Pay later.

This is one of the most common forms of hyperbolic discounting in marketing. You may know it better as the “Buy now! Pay later!” technique.

QVC.com is packed with every manner of marketing techniques. If you want to exercise your delayed gratification muscles, go check them out. Or not.

PayPal’s infamous Bill Me Later program (name now changed) was built on the whole psychological principle of hyperbolic discounting.

Here’s the marketing message of Seventh Avenue. It couldn’t be clearer:

- Send no money

- Buy now

- Pay later

- Couldn’t be easier

- Just start shopping

Montgomery Ward does it, too.

Lurking behind the message is the fact that you’re applying for a credit card. Remember what I told you about credit cards? Yep; built on the power of hyperbolic discounting.

You don’t have to offer credit cards in order to use this technique. You can simply delay payment, allowing the user to make a purchase and wait to pay. It’s risky for you, but it could improve sales.

3. Give an immediate gift.

With hyperbolic discounting, timing is everything. That’s why some people refer to it as temporal discounting. The time element reigns supreme in the buyers’ minds. Rather than wait for any amount of time, they will act willingly to gain something immediately.

In many cases, a simple and inexpensive gift will suffice. Sometimes, users will convert based on the promise of an immediate result, even if the full product is not available until later.

EA Access gives gamers the ability to join a program where the big results aren’t available until later. Gamers are likely to convert, however, because they get immediate access to the vault.

4. Charge a higher price for a shorter term.

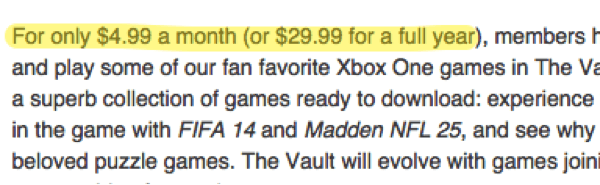

Have you ever noticed that some websites offer payment plans that don’t make financial sense?

Here’s the type of thing they offer:

- Buy 1 month: $9.99

- Buy 1 year: $39.99

Hold on a second! I can do math. I know that there are twelve months in a year. I also know that if one year costs $39.99, then one month at the yearly rate is only $3.33. So, why would anyone pay $9.99 for one month?

Why you ask? Hyperbolic discounting, that’s why. The user wants to pay less now. They don’t want to pay more, even if it results in a discount over the long term. (That would be the case if one month cost $9.99, because then 12 months at that price would cost $119.88, so $39.99 would be a discount.) They are considering the issue from a temporal perspective, not a true value perspective.

Here’s an example:

Grammarly uses this on their pricing page. Users can pay $29.95 each month, or $11.66 per month. Which one would any sane person choose? The 11.66, of course! Ah, but don’t forget about the framing effect. The way in which the price is framed heavily influences how the price is perceived. Thus, when considered as a $139.95 lump sum, users are tentative. They would rather save money now than save money over the long term.

As a conversion optimizer, you can use this technique to your advantage. Users get to choose their payment method. You’re getting more value per order from the short-term pricing option, because buyers are heavily influenced by hyperbolic discounting.

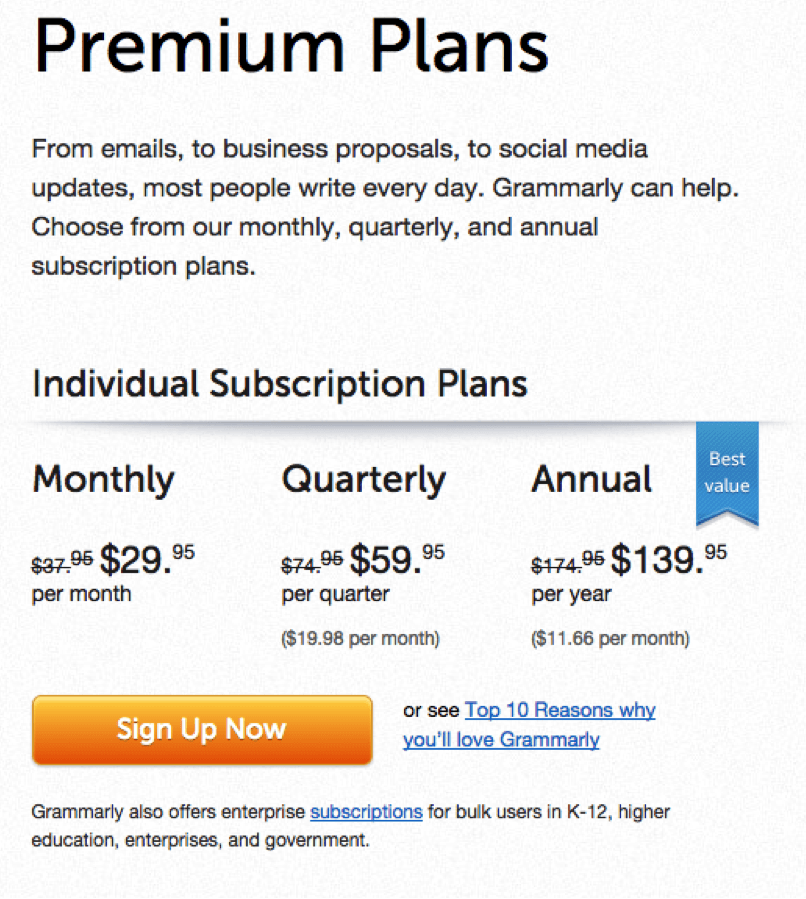

5. Pay for referrals right away.

Online affiliate programs are very popular, but not very strategic. Here’s how they work:

If customers refer friends, then they get money when the friends sign up. Here’s a screen grab from Payoneer:

Nice, huh? Well, not really.

Who wants to wait for their friends to sign up? Even though the payout could be big, the delay is insufferable. Remember, people want it now.

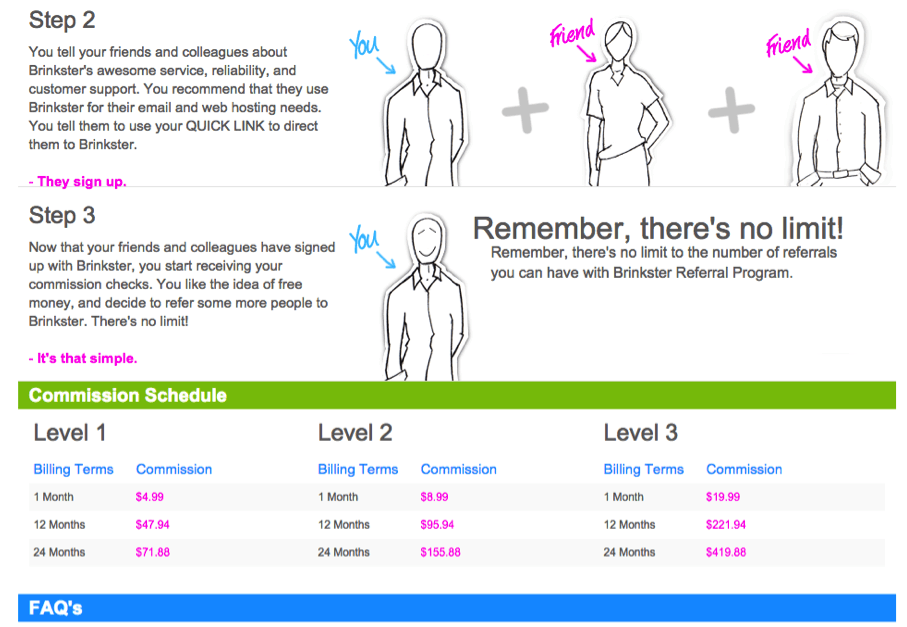

This is how Brinkster does it:

Which is a more strategic approach? Pay people to refer their friends and don’t make them wait for their friends to sign up.

If you offer, say, ten cents for every friend referred, then you can give the referring friend ten bucks. They refer 100 friends!

If you stuck with the old pay-when-they-sign-up model, you may have to pay $10 for only a single referral. With the pay-now model, you can compel the referring friend to make 100 times as many referrals!

The idea here is built off of hyperbolic discounting. A little reward right away is better than a big reward later on.

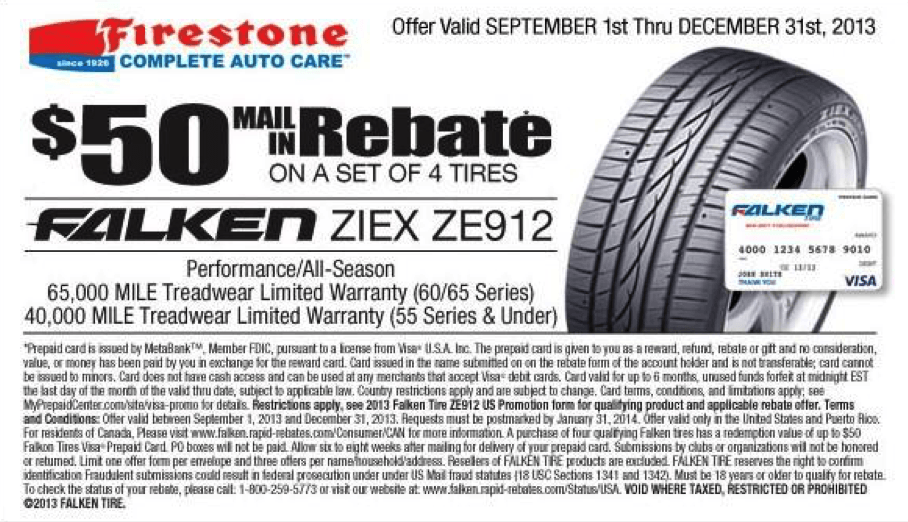

6. Offer mail in rebates.

Why do some retailers offer mail in rebates? The idea is that if you cut some coupon, scan your receipt, and upload them to some agonizing website, you might get a dinky check for a few bucks in the mail in 20-40 weeks.

Is anyone going to do this? I’d rather pay $50 than be subjected to that agony.

Who even has time for that? Do retailers really think that they’re doing you a favor? Of course not. They’re using hyperbolic discounting.

Mail in rebates work for only a select few customers: the disciplined customers who never lose anything, change their oil at the dealership every 3,000 miles, save their receipts in alphabetized file folders, and iron their socks. In other words, not many people.

The built-in draw of hyperbolic discounting is at work again. People are likely to buy the product now, thinking that they might get a discount in the future. More likely than not, that mail in rebate form will languish in a stack of papers until it expires. The retailer doesn’t have to pay anything.

Conclusion

If you want better conversion rates and smart marketing power, then this article was written with you in mind.

I can speak from experience. My clients love me for this. Hyperbolic discounting may sound like jargon, but it’s pure gold.

You can do a couple of things with this article. You can recognize the sinister power of hyperbolic discounting in your own life. (What about that retirement fund, hmmm?) And, you can exercise its impact on conversion optimization. Then, watch those conversion rates rise!